Commentary

Commentary Has Japan become poor?

Ever since the bubble in the 80s, people in Japan have been saying how they are poor now. Sure, compared with the bubble...

Commentary

Commentary  Bank Accounts

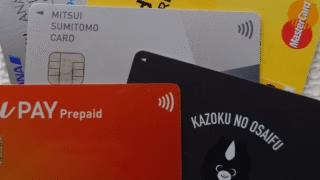

Bank Accounts  Credit Cards

Credit Cards  Gold & Precious Metals

Gold & Precious Metals  Prepaid Cards

Prepaid Cards  Bank Accounts

Bank Accounts  Bank Accounts

Bank Accounts  Bank Accounts

Bank Accounts  Commentary

Commentary